MSc. Data Science Disertation: About AI-Powered Chatbot for University Websites

Date: January 01, 2025

Table of Contents

- Abstract

- Chapter 1: Introduction

- Chapter 2: Background

- Chapter 3: Literature Review

- Chapter 4: Problem Statement

- Chapter 5: Methodology

- Chapter 6: Results

- Chapter 7: Conclusion

- Chapter 8: Further Work

- Chapter 9: References

- Chapter 10: Appendix

Abstract:

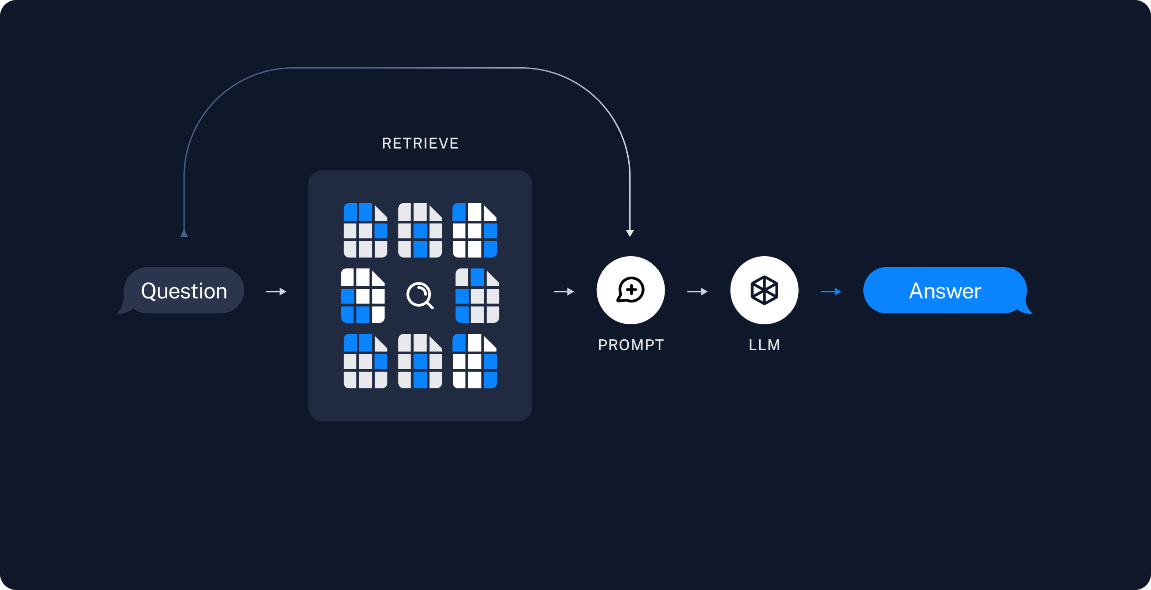

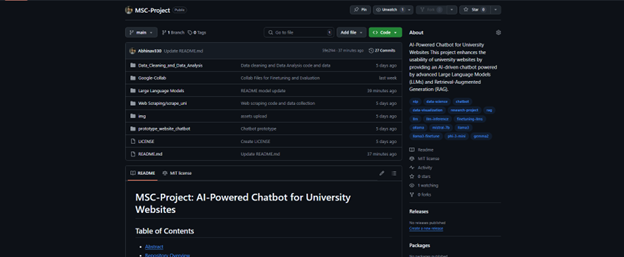

University websites have become essential tools for giving information to diverse audiences, including prospective students, faculty, and stakeholders. However, the usability and efficiency of these platforms often fall short, with users meeting challenges such as complex navigation, fragmented information, and a lack of personalisation. Recent studies emphasise these shortcomings, highlighting how inadequate information quality (Mogaji et al., 2020) and poorly designed search interfaces (Munoz et al., 2019) hinder decision-making and engagement. Integrating AI-powered solutions, such as chatbots, offers a promising avenue to address these issues by providing real-time, interactive assistance. This research focuses on developing an AI-driven chatbot to enhance the university website user experience, particularly in accessing course-related information. Leveraging state-of-the-art Large Language Models (LLMs) and Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) techniques, the chatbot dynamically retrieves and generates contextually relevant responses to user queries. Previous research underscores the potential of AI in education, with studies exploring chatbot adoption factors (Mohd Rahim et al., 2022), pedagogical implications (Klímová and Ibna Seraj, 2023), and their effectiveness in delivering personalised learning experiences (Pérez et al., 2020). However, gaps persist in aligning chatbot capabilities with user needs, particularly in addressing complex queries and ensuring accurate, domain-specific responses. To bridge these gaps, this project employed a structured methodology encompassing data collection, fine-tuning of LLMs, and the implementation of RAG to enhance response precision. Data scraping techniques were used to extract comprehensive course details from the University of Westminster’s website, creating a robust dataset for training the chatbot. Fine-tuned models, including Mistral-7B, Gemma-2-9B, and Llama-3.2, were evaluated using metrics such as ScarBLEU, CER, and Meteor, ensuring optimal performance in terms of accuracy, fluency, and contextual relevance. The RAG framework further augmented the chatbot’s ability to provide accurate and up-to-date responses by integrating external knowledge dynamically. The results demonstrate significant advancements in user experience, with the chatbot addressing critical issues identified in prior studies, such as fragmented information and inconsistent interfaces (Nachmias and Segev, 2003; Wood, 2020). By offering accurate, context-aware responses, the chatbot not only improves information accessibility but also sets a foundation for future research in AI-driven educational tools. This project bridges the gap between technological capabilities and user expectations, aligning with broader trends in enhancing academic digital services (Mardalena and Andryani, 2021). In conclusion, this research highlights the transformative potential of generative AI and RAG in reshaping how educational institutions interact with their stakeholders, addressing longstanding challenges in usability and information delivery.

Chapter 1: Introduction

The digital age has significantly reshaped the higher education landscape, with university websites becoming indispensable tools for information dissemination. These platforms cater to diverse audiences, including prospective students, current enrollers, faculty members, and institutional stakeholders. Despite their importance, numerous studies have highlighted persistent challenges associated with university websites, ranging from difficult navigation and fragmented data to poor search functionalities and a lack of user engagement (Mogaji et al., 2020; Nachmias and Segev, 2003). Such limitations impede users’ ability to access critical information and adversely impact decision-making processes, particularly for prospective students considering enrolment options. Educational institutions have increasingly turned to Artificial Intelligence (AI) technologies to address these challenges. Chatbots have emerged as powerful tools that enhance user interaction by offering real-time, personalized assistance. Unlike traditional interfaces, AI-driven chatbots provide dynamic and context-aware responses, transforming how users access information. However, while chatbots have gained traction across various industries, their application in higher education remains underexplored. Existing implementations often rely on basic models with limited capacity to understand complex queries or adapt to the evolving needs of users, leaving significant gaps in functionality and user satisfaction.

This dissertation investigates the development of an AI-powered chatbot explicitly designed for university websites, focusing on improving access to course-related information. By leveraging state-of-the-art Large Language Models (LLMs) such as Mistral-7B, Gemma-2-9B, and Llama-3.2, this project aims to address critical shortcomings in existing systems. Integrating Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) further enhances the chatbot’s ability to donate, retrieve and generate accurate, domain-specific responses dynamically from prior research on chatbot adoption in educational settings (Mohd Rahim et al., 2022; Pérez et al., 2020), this study explores the transformative potential of generative AI in improving user experience on academic platforms. The objectives of this research are threefold: to design and implement a chatbot capable of providing precise and contextually relevant course information; to evaluate the chatbot’s performance using advanced metrics such as ScarBLEU, CER, and Meteor; and to demonstrate its potential to enhance digital interactions in higher education. By addressing the gaps identified in existing literature, this project aims to contribute to the growing body of knowledge on AI applications in academia, paving the way for more accessible and user-friendly educational platforms.

Chapter 2: Background

The integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in higher education has emerged as a transformative approach to addressing longstanding challenges in information accessibility and user engagement. University websites, serving as the primary touchpoints for disseminating course-related information, often fall short in meeting user expectations. Studies have consistently highlighted issues such as inadequate information quality, fragmented data, and poor usability, which hinder prospective students and other stakeholders from effectively accessing critical details (Mogaji et al., 2020; Nachmias and Segev, 2003). To address these issues, AI-powered chatbots have gained significant attention in recent years. Early implementations focused on rule-based systems with limited functionality, but Natural Language Processing (NLP) advancements have shifted the focus to more sophisticated models. Research by Munoz et al. (2019) underscores the importance of intuitive, user-friendly designs in chatbot interfaces, while Mohd Rahim et al. (2022) emphasize factors influencing chatbot adoption, including trust, interactivity, and performance expectancy. These studies highlight the potential of AI in improving user interactions and delivering personalized, context-aware assistance. Generative AI, particularly Large Language Models (LLMs), represents a significant leap forward in chatbot capabilities. Models such as GPT, BERT, and their successors have demonstrated understanding and generating human-like responses, enabling more dynamic and adaptive user interactions. These models can be customized to address specific domains, such as education by leveraging pre-trained knowledge and fine-tuning techniques. For instance, Klímová and Ibna Seraj (2023) explored the pedagogical implications of chatbots in English as a Foreign Language (EFL) classroom, finding improvements in student motivation, engagement, and learning outcomes. Similarly, Pérez et al. (2020) identified chatbots as effective educational agents capable of providing tailored learning experiences akin to human tutors.

However, the adoption of LLMs in educational chatbots is not without challenges. Issues such as hallucinations, where models generate inaccurate or fabricated information, pose significant risks to reliability (Athaluri et al., 2023). Ethical data privacy and transparency concerns must be addressed to ensure responsible implementation. Research by Gordon and Berhow (2009) highlights the importance of aligning chatbot functionalities with user needs, emphasizing the role of dialogic features in building trust and engagement.

This research builds on existing literature to develop a domain-specific chatbot for university websites, focusing on course-related information. By incorporating Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) techniques, the chatbot dynamically integrates external knowledge into its responses, addressing limitations in static pre-trained models. The findings of this study contribute to a growing understanding of how AI and generative models can transform information delivery in higher education, aligning technological capabilities with user expectations and institutional goals.

Chapter 3: Literature Review

3.1. Role of University Websites in Delivering Course Information.

3.1.1. Introduction

University websites are crucial platforms for disseminating course details and other essential information to students. However, navigating these websites can often take time and effort, leading to inefficiencies and user dissatisfaction. Recent studies have explored the integration of chatbots to enhance user experience by providing real-time, interactive assistance. This literature review examines the current state of university websites for course details, identifies existing gaps, and discusses how chatbots can address these issues.

3.1.2. Review of Existing Research

University websites are crucial in providing course details to prospective and enrolled students. Various studies have explored different aspects of these websites, including the quality of information, usability, and the effectiveness of search tools.

3.1.2.1. Information Quality and Accessibility:

A study assessing African universities’ websites found that the information about undergraduate programs needed to be more often sufficient for prospective students to make informed decisions. The study utilised the ALARA Model of Information Search and highlighted the need for universities to improve the quality and quantity of online information (Mogaji, Amarachukwu Anyogu and Wayne, 2020).

3.1.2.2. Semi-automated Syllabus Crawling:

Research on the websites of 100 universities focused on enabling semi-automatic crawling of course syllabi. The study categorised syllabus pages into three types: Link Type, Whole Type, and Database Type. It found that semi-automatic crawling could significantly improve by identifying key pages using a linear support vector machine (Sekiya, Matsuda and Yamaguchi, 2019).

3.1.2.3. Comparison of Course Search Interfaces:

A comparative study of course search tools at three universities (University of Nevada, Reno, Harvard University, and University of California, Berkeley) revealed that students preferred simpler designs with clear layouts. The study emphasised the importance of user-friendly interfaces for effective course searches (Munoz et al., 2019).

3.1.2.4. Student and Faculty Perceptions:

A year-long study at the United States Military Academy found a gap between what faculty members thought was beneficial on course websites and what students used. Students primarily accessed basic features like test preparation materials and administrative information, while more advanced features were underutilised (Braddom et al., 2020).

3.1.2.5. Content Usage in Web-supported Courses:

An investigation into the use of online content in academic courses showed significant variability in how students accessed and used the materials. The study used computer logs to track content usage and highlighted the importance of understanding these patterns for better website design (Nachmias and Segev, 2003).

3.1.2.6. Dialogic Features for Relationship Building:

A content analysis of 232 university websites using Kent and Taylor’s dialogic principles found that liberal arts institutions and Tier 3 universities used more dialogic features. These features were correlated with higher student retention and alums giving rates (Gordon and Berhow, 2009).

3.1.2.7. Student Opinions on Departmental Websites:

A survey of English significant students revealed that departmental websites often fail to meet student expectations. The study suggested that universities need to improve their websites to better align with student needs and preferences (Zengin, Arikan and Dogan, 2011).

3.1.2.8. Information Quality and Enrolment Interest:

A study investigating the relationship between the quality of information on academic department websites and student interest in enrolment found a strong correlation. The study used accuracy, consistency, completeness, and timeliness to gauge information quality (Wood, 2020).

3.1.2.9. Website Service Quality Analysis:

An analysis of the Palembang Open University’s website using the Webqual 4.0 method and Importance Performance Analysis (IPA) found that the website’s performance needed to meet user expectations fully. The study identified areas needing improvement to enhance user satisfaction (Mardalena and Andryani, 2021).

3.1.3. Bridging Challenges in University Websites with Technological Solutions

Despite extensive research on university websites, significant challenges persist in effectively delivering course details to prospective students. Many universities fail to provide comprehensive and easily accessible information, hindering students from making well-informed decisions (Mogaji, Amarachukwu Anyogu, and Wayne, 2020; Wood, 2020). User-friendly interfaces are essential, yet many university websites continue to suffer from complex and cluttered designs that impede efficient navigation and information retrieval (Arikan, Dogan, and Zengin, 2011; Munoz et al., 2019). Moreover, a disconnect often exists between faculty expectations and student usage patterns, highlighting a lack of alignment between website features and student preferences (Nachmias and Segev, 2003; Braddom et al., 2020). Automated solutions for information retrieval, such as semi-automatic crawling of course syllabi, remain underdeveloped, pointing to the need for more advanced tools (Sekiya, Matsuda, and Yamaguchi, 2019). Additionally, while some universities incorporate dialogic features to foster stronger relationships with students, many fail to fully capitalise on these opportunities, limiting engagement and retention potential (Gordon and Berhow, 2009). The lack of systematic processes for continuous quality assurance in website content further exacerbates the issue, often leading to outdated or inconsistent information (Mardalena and Andryani, 2021).

To address these gaps, chatbots have emerged as a promising solution. By providing instant, user-friendly access to comprehensive course details, chatbots can enhance personalised information retrieval and bridge the gap between user needs and website features. These tools not only streamline navigation but also support real-time engagement, making them an asset for universities aiming to improve their digital offerings (Bill, 2013).

3.2. Integration of Chatbots in Higher Education

The adoption of chatbots in higher education institutions (HEIs) has been a growing area of interest, particularly in improving student services and educational outcomes. Several studies have explored various aspects of this adoption, focusing on factors influencing effectiveness, user acceptance, and pedagogical implications.

3.2.1. Research Contributions

3.2.1.1. Factors Influencing Chatbot Adoption:

A study focusing on adopting AI-based chatbots in Malaysian universities highlighted that perceived trust, influenced by interactivity, design, and ethics, plays a crucial role in the behavioural intention to use chatbots. Additionally, performance expectancy and habit were significant predictors of chatbot adoption in the educational context (Mohd Rahim et al., 2022). Another study explored the role of perceived convenience and enhanced performance in adopting chatbots for learning among university students, emphasising the importance of these factors in making learning more effective (Malik et al., 2021). Furthermore, the acceptance of ChatGPT by university students was influenced by experience, performance expectancy, hedonic motivation, price value, and habit, indicating that these factors are critical in shaping user behaviour towards chatbot adoption (Romero et al., 2023).

3.2.1.2. Pedagogical Implications and Learning Outcomes:

The integration of chatbots in educational settings has significant pedagogical implications and can positively impact learning outcomes. A mini-review on using chatbots in university EFL (English as a Foreign Language) settings found that chatbots enhance effectiveness, motivation, satisfaction, exposure, and assessment in language learning. The study also highlighted the potential of chatbots to apply and integrate existing theories and concepts used in EFL teaching, such as CEFR and self-regulatory learning theory, thereby contributing to more effective teaching and learning (Klímová and Ibna Seraj, 2023). Another study proposed a theoretical framework for blended learning with intelligent chatbots, facilitating interactive learning experiences and helping instructors manage courses more efficiently. This framework underscores the transformative potential of AI chatbots in education and their ability to enhance the overall educational experience (Ilieva et al., 2023). A systematic literature review also identified that chatbots could function as educational agents, providing personalised learning experiences like human tutors, which can significantly improve learning outcomes (Pérez, Daradoumis and Puig, 2020).

3.2.1.3. Academic Advising and Library Services:

Chatbots have also been explored for their potential in academic advising and library services. A study on robo-academic advisors reviewed the literature on chatbots and AI in auto-advising systems, finding that chatbots can effectively balance personalised student advising with automation. The study emphasised the need for more empirical research to understand the effectiveness of chatbots in academic advising and how they can be integrated into educational settings (Mohammed Muneerali Thottoli, Badria Hamed Alruqaishi and Arockiasamy Soosaimanickam, 2024). In the context of academic libraries, a qualitative study explored the perceived risks and challenges of adopting chatbots. The findings suggested that stakeholders, including library staff, doctoral students, and faculty, generally Favor the adoption of chatbots, as they believe these tools can enhance library services and support research and scholarly communication. However, concerns about privacy and the chatbots’ ability to comprehend complex tasks were highlighted as issues that need to be addressed (Kaushal and Yadav, 2022). Another review of the opportunities and challenges of chatbots in education noted that chatbots could significantly improve library services by providing real-time assistance and information to users, thereby enhancing the overall user experience (Hwang and Chang, 2021).

3.1.2. Techniques and Methodologies

The development of university chatbots has leveraged various techniques, ranging from natural language processing (NLP) and neural networks to hybrid modelling approaches and pedagogical frameworks. NLP is pivotal in enabling chatbots to interpret and generate human-like responses. For instance, Bhartiya et al. (2019) describe an auto-reply bot for university counselling that uses NLP on JSON-formatted university data. The chatbot employs a feedforward neural network, addressing challenges such as overfitting to enhance response accuracy. Similarly, Mangotra et al. (2024) explore two deep learning models—a bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) network and a simple feedforward neural network—for a chatbot answering university-related queries. Their study underscores the significance of self-curated datasets and NLP preprocessing for handling raw data effectively. Another survey by Rakesh et al. (2022) highlights the role of NLP in creating an academic chatbot capable of addressing academic and non-academic queries and ensuring instant access to relevant information. Beyond NLP and neural networks, hybrid models have been employed to understand factors influencing chatbot adoption in higher education institutions (HEIs). Mohd Rahim et al. (2022) integrate a hybrid PLS-SEM-Neural Network approach, guided by the UTAUT2 model, to analyse the effectiveness of chatbot adoption. This approach combines statistical and machine learning techniques to provide robust insights into user engagement and system efficiency. Additionally, the pedagogical implications of chatbots in university settings have been explored. Klímová and Ibna Seraj (2023) focus on applying chatbots in English as a Foreign Language (EFL) classroom, evaluating their impact on student motivation, satisfaction, and effectiveness. By integrating frameworks like the Common European Framework of Reference (CEFR) and self-regulatory learning theory, this research aligns chatbot functionality with established educational principles to enhance learning outcomes. Collectively, these techniques highlight the diverse strategies adopted in building and optimising university chatbots, addressing both technical and pedagogical aspects to ensure their effectiveness in higher education contexts.

3.1.3. Bridging Research Gaps and Shaping the Future of Chatbot Integration in Education

Despite advancements in chatbot technology, several critical research gaps remain in their adoption within educational settings. The accuracy and efficiency of chatbot responses require further enhancement, as demonstrated by a study where initial response accuracy score d 0.46, improving to 0.72 with additional training, emphasizing the need for continuous dataset and algorithm refinement (Bhartiya et al., 2019). Furthermore, comprehensive adoption models explicitly tailored for student services are lacking. Most studies highlight the benefits of chatbots without leveraging structured information systems (IS) theories to explore the factors influencing their adoption in higher education institutions (HEIs) (Mohd Rahim et al., 2022). Research into behavioural intentions and user experience is also limited, with few studies categorizing findings based on theoretical models, research methods, and adoption factors. This underscores the need for more holistic research to better understand user behaviour and experience (Gatzioufa and Saprikis, 2022). Additionally, while chatbots are prevalent in the service industry, their integration into educational contexts for effective learning remains underexplored, highlighting a gap in research on their role in enhancing e-learning platforms (Malik et al., 2021).

Generative AI and Large Language Models (LLMs) present promising solutions to these challenges. By leveraging LLMs, educational institutions can develop sophisticated chatbots capable of delivering accurate, context-aware, and efficient responses. These models can significantly enhance user experiences, align with behavioural expectations, and integrate seamlessly into educational and e-learning platforms, ultimately improving learning outcomes (Noy and Zhang, 2023). Moreover, their adaptability and capacity for continuous learning can support the development of more comprehensive and effective adoption models, bridging the gap between research and practical application.

3.3. Leveraging Generative AI and Large Language Models for Chatbots

The integration of large language models (LLMs) and generative AI in university chatbots has been a subject of growing interest. Several studies have explored the potential and challenges of these technologies in educational settings.

3.3.1. Research Analysis

3.3.1.1. Capabilities and Applications

Generative AI, particularly models like OpenAI’s ChatGPT, has demonstrated significant potential in enhancing educational tools. For instance, ChatGPT has generated virtual patient simulations, quizzes, and even draft calls for academic papers, showcasing its versatility in medical education(Eysenbach, 2023). Similarly, the use of generative AI in creating pedagogical conversational agents has been investigated, highlighting the flexibility and trustworthiness of these models compared to traditional knowledge-based systems (Wölfel et al., 2023). These studies underscore the transformative impact of LLMs in creating interactive and adaptive learning environments.

3.3.1.2. Comparative Studies and Evaluations

Research has also focused on evaluating the performance of AI-driven chatbots in academic contexts. A comparative study assessed the quality of scientific abstracts and references generated by different versions of AI chatbots, revealing that while the content quality was average, there was a notable issue with hallucinations, where the AI-generated unverifiable references (Hua et al., 2023). This finding is critical as it points to the need for caution when relying on AI-generated content for academic purposes.

3.3.1.3. Ethical and Practical Considerations

The ethical implications of using generative AI in academia have been discussed. The potential for AI to generate fake research and the importance of transparent use and open science practices have been highlighted as crucial considerations (Lin, 2023). Additionally, AI hallucination, where the model generates inaccurate or fabricated information, has been identified as a significant challenge that must be addressed to ensure the reliability of AI-generated content (Athaluri et al., 2023).

3.3.2. Research Gaps and Limitations

Despite the promising applications of generative AI in educational chatbots, several gaps and challenges still need to be addressed.

3.3.2.1. Hallucination and Misinformation

One of the most pressing issues is the tendency of generative AI models to hallucinate, producing content that deviates from their training data. Numerous studies have documented this problem, with AI-generated references often being unverifiable or entirely fabricated (Athaluri et al., 2023; Eysenbach, 2023; Hua et al., 2023). The high hallucination rates seen in these studies show a need for improved training data and more robust verification mechanisms to ensure the accuracy of AI-generated content.

3.3.2.2. Ethical and Legal Concerns

The ethical and legal implications of using AI in academic settings also require further exploration. The potential for AI to worsen inequalities and the need for transparent disclosure of AI assistance in research are critical issues raised (Lin, 2023; Lund et al., 2023).s Addressing these concerns is essential to ensure AI’s responsible and fair use in education.

3.3.2.3. Domain-Specific Adaptation

While generative AI models offer flexibility, their adaptation to specific domains often creates a trade-off between flexibility and correctness. The limited amount of domain-specific data can constrain the accuracy of the responses generated by these models, highlighting the need for more robust training datasets and improved adaptation techniques (Wölfel et al., 2023).

3.3.3. Future Directions and Potential Solutions

One promising solution to address the issue of hallucination in generative AI is Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) tuning. RAG combines the strengths of retrieval-based and generative models by incorporating a retrieval component that fetches relevant information from a large corpus of documents, which the generative model then uses to produce more accurate and reliable outputs. Recent studies have shown that implementation of RAG tuning can improve the performance of AI by 33% to 42%. This approach can significantly reduce the likelihood of hallucinations and improve the overall reliability of AI-generated content (I et al., 2023).

3.4. Conclusion.

In conclusion, while university websites have come a long way, they still need help finding relevant information, like inaccurate search results and difficulty finding relevant information, which can frustrate users. Previous studies have looked at AI solutions, such as chatbots. Still, many of these systems use basic models that do not handle complex user queries or the constantly changing nature of educational content well. This project aims to bridge that gap by creating an AI-powered chatbot using advanced large language models (LLMs) and retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) techniques. This work builds on existing research by improving how information is retrieved and providing more accurate, context-aware responses. It addresses the shortcomings of current university websites, improving the user experience.

Chapter 4: PROBLEM STATEMENT

University websites are integral platforms that provide vital information to students, faculty, and prospective applicants. However, navigating these websites often presents significant challenges. Users frequently need help with issues such as fragmented information, outdated interfaces, and inefficient search functionalities, making it difficult to access specific course-related details promptly. This lack of accessibility hampers user experience and can adversely influence prospective students’ decisions. Traditional search mechanisms on university websites often fail to deliver accurate and relevant results, primarily due to poorly structured data and limited search capabilities. The complexity of university websites, with extensive amounts of information spread across multiple pages, exacerbates these issues. Moreover, the absence of personalised assistance leaves users to navigate the website independently, leading to frustration and decreased engagement.

Integrating AI-driven chatbots offers a promising solution to these challenges by providing interactive, efficient, and personalised access to information. However, developing a chatbot encompassing the entire breadth of university data requires substantial computational resources and significant capital investment, which may not be feasible within the scope of this research project. Therefore, this project focuses on course-related information, aiming to develop an AI-powered chatbot that can accurately and efficiently provide users with the course details they seek. The project aims to improve user experience without incurring prohibitive costs by concentrating on this critical aspect of university websites.

Additionally, the chatbot deployment is beyond this research’s scope. Deployment involves considerations that are not directly related to data science, such as infrastructure setup, maintenance, and scalability issues. It also requires investment in GPU-enabled servers to host and run the model effectively, which entails significant costs. Therefore, the project will concentrate on developing and evaluating the chatbot within a controlled environment, emphasising data science aspects such as data collection, model training, and performance evaluation.

4.1. OBJECTIVES

This research aims to develop an AI-driven chatbot designed to improve the user experience on the University of Westminster website by focusing exclusively on course-related information. Given the constraints of computational resources and financial feasibility, the research narrows its scope to this critical area, ensuring the project remains achievable within the given parameters. The specific objectives include:

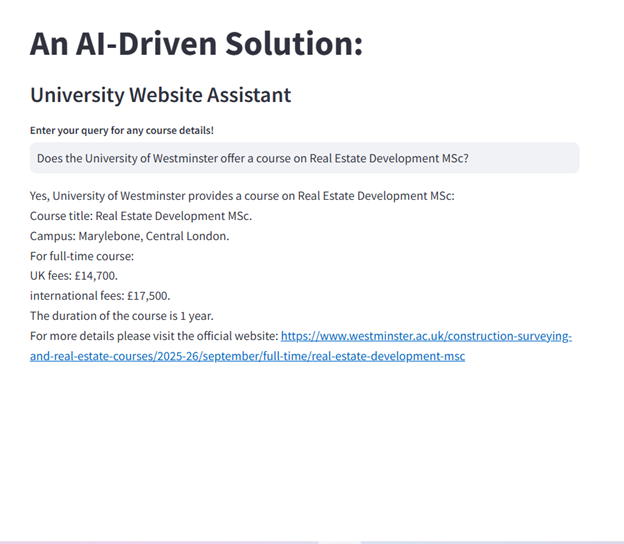

Development: Design and implement a chatbot that accurately retrieves and delivers course-related information, such as program titles, durations, fees, and campus details. By concentrating on course data, the project minimizes computational costs and focuses on enhancing accessibility in this essential area.

Improving User Experience: Simplify the process of obtaining course information by providing a conversational interface that eliminates the need for users to navigate complex website structures. The chatbot will function as a virtual assistant, ensuring the responses are clear, contextually relevant, and tailored to user needs, thus enhancing the overall user experience.

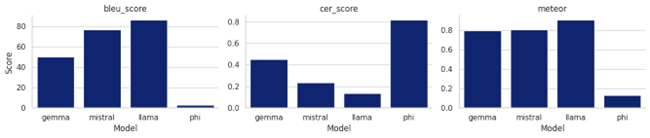

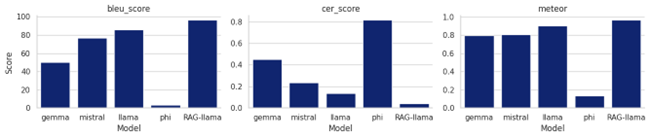

Model Evaluation and Selection: Train and evaluate multiple LLMs, including Mistral 7B, Gemma 9B, Phi 3.5, and Llama 3.2, to determine the most suitable model for this focused task. The evaluation process will include metrics such as ScarBLEU, CER, and Meteor scores, ensuring accuracy, fluency, and reliability in the chatbot’s responses.

Exploring Academic Applications: Demonstrate the utility of AI in enhancing user interactions with educational websites. By highlighting the effectiveness of AI-driven chatbots in improving accessibility and usability, this project provides a foundation for future research and applications in academic settings.

4.2. PLAN OF WORK

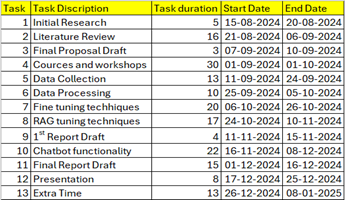

The project follows a structured and well-defined plan of work, reflecting the focused scope and resource-conscious approach outlined in the proposal:

4.2.1. Project Management:

To ensure timely and efficient delivery, the project followed an Agile methodology, enabling iterative development and frequent feedback loops. The work plan was organized into sprints, with milestones tracked using a detailed Gantt chart. Regular meetings with the project supervisor facilitated progress updates, troubleshooting, and strategic adjustments. For detailed project management strategies, refer to Appendix 1.

4.2.2. Data Collection:

Scrape the University of Westminster website using Python’s Scrapy framework, focusing on extracting structured information related to courses. Data fields include course titles, descriptions, durations (full-time, part-time, and distance learning), fees (UK and international), campuses, and URLs. To ensure ethical data collection, the scraping process incorporates time delays, proxy headers, and adherence to the website’s policies.

4.2.3. Data Cleaning and Preparation:

Once the data is collected, pivot tables consolidate duplicate entries, ensuring each row corresponds to a single course with all related details. The data will be pre-processed to remove inconsistencies, fill in missing values, and standardise the format, creating a structured CSV file with clearly defined columns for attributes like course title, duration, fees, and URLs.

4.2.4. Model Selection and Fine-Tuning:

Identify pre-trained LLMs such as Mistral 7B, Gemma 9B, Phi 3.5, and Llama 3.2 for experimentation. Fine-tune the selected models on the prepared course dataset using Google Collab with A100 GPUs, applying parameter-efficient techniques to minimise computational demands. Training processes will emphasise cost-effectiveness without compromising model quality. Metrics like ScarBLEU, CER, and Meteor scores will be used to evaluate model performance, ensuring the chatbot generates accurate and contextually relevant responses.

4.2.5. Chatbot Prototype Development:

Develop a prototype chatbot interface to interact with the fine-tuned model in a local environment. LangChain will build the conversational framework, while Chroma Database will efficiently store and retrieve course-related information. Streamlit will create a simple and accessible user interface for testers to engage with the chatbot and evaluate its functionality.

4.2.6. Testing and Evaluation:

Conduct comprehensive testing of the chatbot to ensure it handles various user queries effectively, including paraphrased and complex questions. Develop a detailed set of test cases to validate the chatbot’s performance, focusing on response accuracy, relevance, and clarity. Document the testing process, analysing results to identify strengths and areas for improvement.

4.2.7. Risk Management :

Effective risk management is crucial to the success of this project. Key risks identified include data limitations, resource constraints, model performance issues, and ethical concerns. To mitigate these risks, rigorous data preprocessing and cleaning will ensure the dataset’s reliability and consistency. Resource limitations are addressed through parameter-efficient training techniques such as LoRA and selective dataset fine-tuning. Regular testing with diverse queries will help improve model performance, identifying and resolving potential issues. Ethical compliance is maintained by following website scraping policies and ensuring responsible AI usage. For detailed risk management strategies, refer to Appendix 2.

Chapter 5: METHODOLOGY

This section describes the data sources utilized in this research project, focusing on creating a comprehensive dataset for training and evaluating the AI-driven chatbot. The data sources span three key areas: the primary dataset obtained through web scraping, the large language models used, and the infrastructure supporting Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) tuning.

5.1. Data Sources

5.1.1. Primary Dataset:

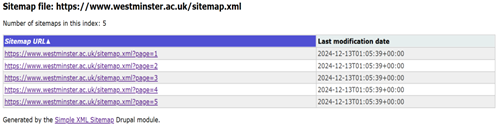

The primary dataset for this project was sourced by scraping the University of Westminster’s official website. The objective was to extract course-related information for developing an AI-powered chatbot capable of answering queries about university programs. The site’s structure was analysed using the website’s sitemap (Figure 1), and pages relevant to course information were identified and accessed. The scraping process was selective to ensure that only data about course offerings was collected, thus maintaining focus and optimizing resource utilization.

Figure 1: sitemap for the University of Westminster website.

Figure 1: sitemap for the University of Westminster website.

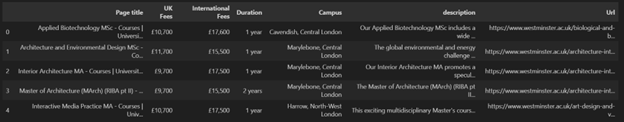

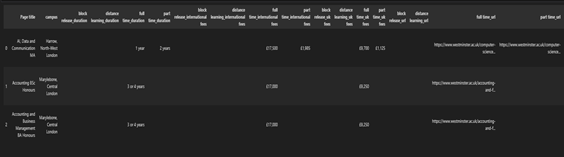

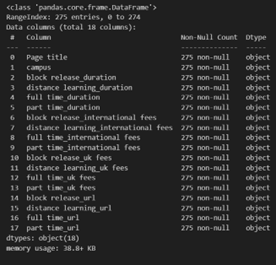

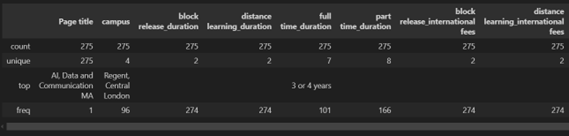

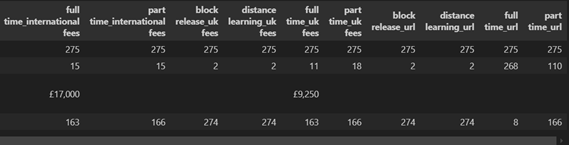

The dataset includes several key attributes (Figure 2), such as course titles, descriptions, UK tuition fees, international tuition fees, duration (full-time, part-time, distance learning), and campus locations. These fields were chosen to ensure comprehensive coverage of user queries regarding the university’s courses. The final dataset was stored in a structured CSV file, providing a robust foundation for subsequent fine-tuning of the chatbot’s models. This carefully curated dataset enables the chatbot to provide accurate and contextually relevant responses. For more information about dataset and code base refer to Appendix 3.

Figure 2: Dataset

Figure 2: Dataset

5.1.2. Large Language Models (LLMs):

The project leveraged open-source pre-trained Large Language Models (LLMs) available on Hugging Face, a platform for hosting state-of-the-art machine learning models. Several models were selected based on their suitability for text generation tasks, including Phi-3.5-mini-instruct by Microsoft, Mistral-7B-v0.3 by Mistral AI, Gemma-2-9B by Google, and Llama-3.2-3B by Meta. Each model was fine-tuned using the curated dataset to effectively enhance its performance in answering course-related queries.

Among the selected models, the best-performing one was optimized by converting it into the .gguf format. This conversion allowed efficient usage on local systems without requiring extensive computational resources. To facilitate offline accessibility and cost-effective deployment, OLlama was used to host the fine-tuned model locally. This approach ensured that the chatbot could operate independently of cloud-based servers, aligning with the project’s focus on resource optimization and practical deployment.

5.1.3. Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) Tuning:

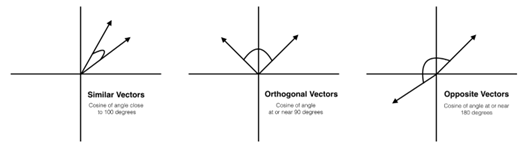

To improve the chatbot’s ability to provide accurate and context-aware responses, Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) tuning was implemented. This advanced methodology combines the strengths of retrieval-based and generative models, allowing the chatbot to incorporate external knowledge dynamically during response generation. In this project, ChromaDB was utilized as the vector database to store embeddings, enabling efficient search based on cosine similarity. The RAG framework enables the chatbot to retrieve the most relevant information from stored embeddings and integrate it into its responses. This capability enhances the accuracy of the chatbot’s answers and ensures adaptability to dynamic user queries. The integration of RAG tuning makes the chatbot more robust, particularly in scenarios requiring access to the latest or highly specific data without frequent retraining.

5.2. IMPLEMENTATION

5.2.1. Web Scraping:

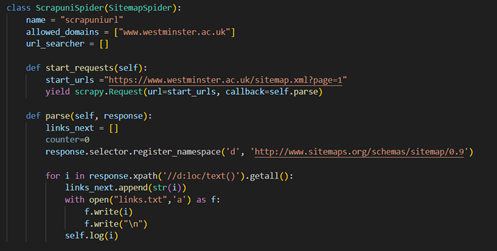

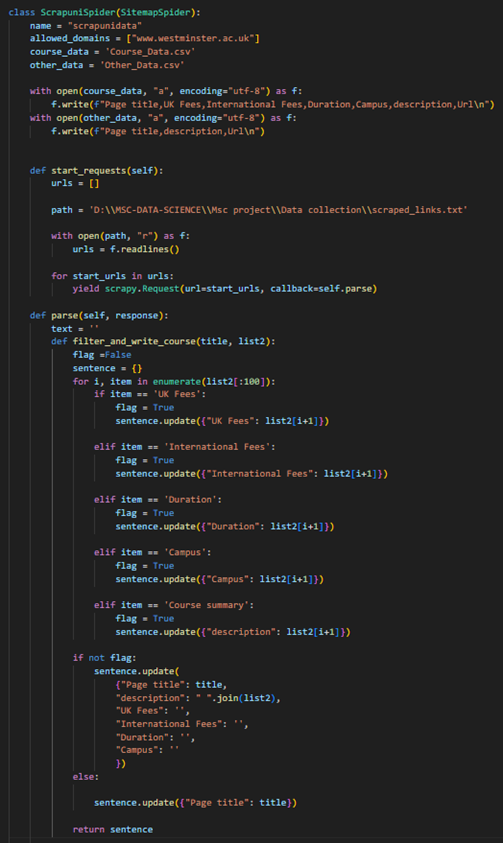

This project’s data collection process began with web scraping, utilizing the Scrapy library for its powerful and flexible capabilities in handling large-scale data extraction. The official University of Westminster website was targeted to gather comprehensive course-related information. The scraping workflow consisted of two distinct spiders, each serving a specific technical purpose: a sitemap crawler (Spider 1) and a data extractor (Spider 2). This modular approach ensured efficient crawling and precise data extraction. Spider 1 was designed as a sitemap spider (Figure 3) to traverse the structured sitemap of the university’s website. The sitemap provides a hierarchical site representation, listing all accessible URLs systematically. This spider leveraged XPath queries to parse the sitemap and extract the URLs for all pages. These URLs were then saved to a text file for further processing. The implementation of this spider included registering the sitemap namespace (http://www.sitemaps.org/schemas/sitemap/0.9) to handle XML-based sitemaps effectively. This modularity allowed Spider 1 to be the backbone for identifying potential data sources across the website, ensuring no relevant pages were overlooked. On the other hand, spider 2 (Figure 4) functioned as the data extractor, specifically targeting pages containing course-related information. The URLs generated by Spider 1 were fed into Spider 2 for deeper exploration. This spider was programmed with custom logic to identify and extract specific data fields critical to the project, such as course titles, descriptions, UK fees, international fees, duration, and campus information. To achieve this, Spider 2 parsed the HTML structure of each page and implemented filtering mechanisms to differentiate between course pages and other irrelevant content. Additionally, error handling and logging were incorporated to manage exceptions and track the scraping progress efficiently.

Figure 3: Code for sitemap crawler.

Figure 3: Code for sitemap crawler.

Figure 4: Code for web page data extractor crawler.

Figure 4: Code for web page data extractor crawler.

The extracted data was processed and stored in a structured CSV file (Figure 5), preserving the integrity and usability of the dataset for subsequent steps in the project pipeline. Combining the broad coverage of a sitemap spider with the precision of a data extractor ensured that the data collection process was both exhaustive and accurate. More details on the scripts are available in Appendix 3.

Figure 5: The CSV file with Data extracted from the website.

5.2.2. Data Cleaning

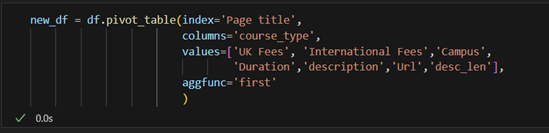

After successfully extracting the raw course-related data from the University of Westminster’s website, the next critical step was data cleaning. This process ensured the dataset was structured, consistent, and ready for analysis and model training. The tools used for data cleaning included Pandas and NumPy, two widely utilized Python libraries for data manipulation and numerical processing. The cleaning workflow was conducted in Python 3.11, using VS Code and Jupyter Notebook for interactive data exploration and debugging. The raw data extracted during the web scraping phase was initially loaded into a Pandas DataFrame for inspection. The first step involved a comprehensive check for missing values across all columns, which revealed no null entries in the raw dataset. Despite missing values, the dataset presented duplicate entries for some courses due to multiple program types (e.g., full-time, part-time, and distance learning). This redundancy stemmed from the page-level data extraction approach, where each program type was represented as a separate entry. A pivot table (Figure 6) was employed to resolve this issue and consolidate all course-related information into a single row. The pivot operation reorganized the data by indexing it on the Page Title (course name) and creating separate columns for each program type, such as UK Fees, International Fees, Campus, Duration, and Course Description. This transformation enabled all relevant details for a course to be represented compactly and comprehensively.

Figure 6: Implementation of pivot table.

Figure 6: Implementation of pivot table.

The pivot table operation introduced null values where data for certain program types was unavailable. All null values were replaced with blank strings to address this, ensuring uniformity across the dataset. This final step eliminated inconsistencies and created a clean, structured dataset suitable for analysis and fine-tuning (Figure 7). The cleaned dataset was saved as a new CSV file, preserving the updated structure for subsequent project stages.

Figure 7: Cleaned Dataset

Figure 7: Cleaned Dataset

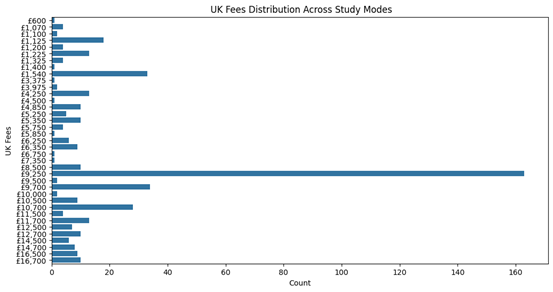

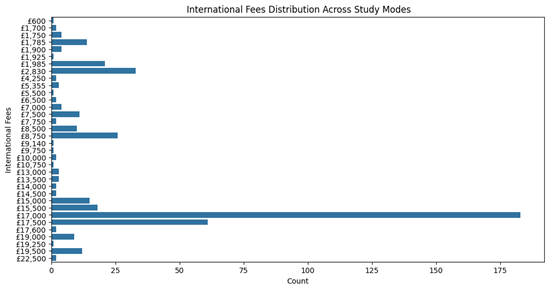

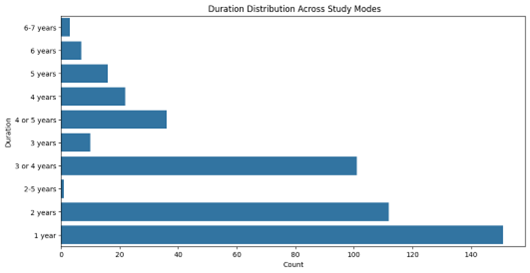

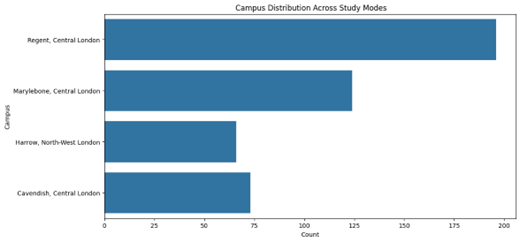

5.2.3. Exploratory Data Analysis

Exploratory Data Analysis (EDA) is an essential preliminary step in validating and understanding the dataset to ensure it meets the requirements for fine-tuning the generative AI model. Although the primary objective of this project is to develop a chatbot for university course-related queries, ensuring the integrity of the dataset is critical to achieving accurate and contextually relevant responses. EDA is particularly beneficial in identifying potential data quality issues, exploring patterns, and summarizing the dataset’s key attributes (Tukey, 1977). The purpose of conducting EDA in this project is twofold. First, it allows for thoroughly examining the scraped and cleaned dataset to confirm its alignment with the chatbot’s functional requirements. Through visualization techniques such as bar charts and histograms, EDA clarifies the distribution of key attributes such as tuition fees, course duration, and campus offerings. For example, analysing the fee distribution ensures that the data accurately reflects the university’s pricing structure, minimizing the risk of misinforming users (Patil, 2018). Second, EDA facilitates the identification of meaningful trends and insights, which can enhance the chatbot’s capabilities. Understanding patterns in tuition fees or course durations enables the chatbot to address user queries more effectively. Additionally, visual summaries offer a way to present the dataset to stakeholders in a clear and accessible manner. This ensures the data preparation process is transparent and aligned with the project’s goals. While EDA does not directly influence the training process of the generative AI model, its role in validating and understanding the dataset makes it an integral part of the project. The Results section will detail findings from the EDA, including visualizations and statistical insights, to demonstrate the dataset’s reliability and implications for the chatbot’s performance.

5.2.4. Model Selection

5.2.4.1 History of Natural Language Processing (NLP)

The evolution of Natural Language Processing (NLP) has been marked by significant breakthroughs in understanding and generating human language. This progression can be divided into five key stages, each contributing to the capabilities of modern NLP systems.

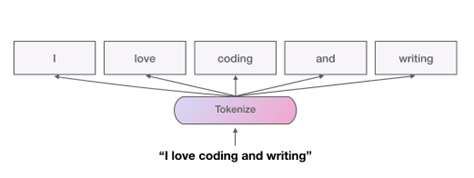

5.2.4.1.1. Foundational Techniques in NLP

The earliest developments in Natural Language Processing (NLP) relied on foundational linguistic techniques, such as tokenization and lemmatization. These methods were pivotal in enabling machines to process and analyse human language. Tokenization (Figure 8) involves breaking down text into smaller units or tokens, such as words or phrases, providing a structured format for computational processing. On the other hand, lemmatization (Figure 9) reduces words to their base or dictionary form, ensuring uniformity in linguistic analysis. For instance, the words “running,” “ran,” and “runs” would all be reduced to their root form, “run.” These techniques laid the groundwork for text analysis by providing the means to parse, process, and normalize text, facilitating early computational applications like search engines and keyword extraction.

Figure 8: Working of Tokenizer (GitHub, 2024)

Figure 8: Working of Tokenizer (GitHub, 2024)

Figure 9: working of Lemmatization (GitHub, 2024)

Figure 9: working of Lemmatization (GitHub, 2024)

5.2.4.1.2 Advancements in Statistical Models

As NLP progressed, statistical methods emerged to enhance text representation and analysis. The Bag of Words (BoW) model became one of the earliest and most straightforward approaches to representing text data numerically. BoW represents a document as a vector of word frequencies, disregarding grammar and word order. While adequate for basic tasks, it could not capture contextual relationships between words. TF-IDF (Term Frequency-Inverse Document Frequency), as illustrated in Figure 10, was introduced to address this limitation, assigning weights to words based on their importance within a document and across the dataset. This innovation allowed models to focus on distinctive terms rather than frequently occurring ones. Another significant advancement was the introduction of n-grams, which extended the BoW approach by capturing sequences of adjacent words. For example, bi-grams and tri-grams allowed models to consider word pairs or triplets, offering limited contextual understanding. These statistical models marked a shift from purely linguistic approaches to computational methods, paving the way for machine learning in NLP.

Figure 10: The TD-IDF technique working in NLP (Anupama Garla, 2021).

Figure 10: The TD-IDF technique working in NLP (Anupama Garla, 2021).

5.2.4.1.3. Neural Word Embeddings: Word2Vec

The advent of Word2Vec (Figure 11) in 2013, developed by Mikolov, revolutionized NLP by introducing word embeddings, a dense and distributed representation of words in a continuous vector space. Unlike previous methods, Word2Vec captured semantic relationships between words. For instance, the model could understand that the relationship between “king” and “man” is similar to the relationship between “queen” and “woman.” Skip-Gram and Continuous Bag of Words (CBOW) achieved this using two key architectures. Skip-Gram predicted context words given a target word, while CBOW predicted a target word based on its context. By training on large corpora, Word2Vec allowed models to encode meaningful relationships, such as word analogies and significantly improved downstream tasks like sentiment analysis, clustering, and recommendation systems. This breakthrough marked the transition from statistical representations to neural approaches, enabling richer language understanding.

Figure 11: working of word2vec algorithm (Logunova, 2023).

Figure 11: working of word2vec algorithm (Logunova, 2023).

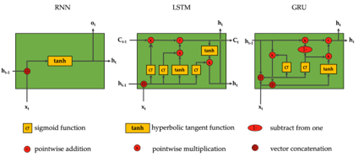

5.2.4.1.4. The Introduction of Deep Learning Models

Deep learning brought a paradigm shift to NLP with the introduction of models such as Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs), Long Short-Term Memory Networks (LSTMs), and Gated Recurrent Units (GRUs). These architectures were designed to handle sequential data, capturing dependencies over time (Figure 12). RNNs were the first neural models capable of maintaining hidden states, enabling them to model sequential relationships. However, RNNs suffered from the vanishing gradient problem, which hindered their ability to learn long-term dependencies. To address this issue, LSTMs introduced memory cells and gating mechanisms, allowing the selective retention or forgetting of information. This made LSTMs particularly effective for tasks like language modelling and text generation. GRUs, a simplified variant of LSTMs, further reduced computational complexity while maintaining comparable performance. Despite their advancements, these models relied on sequential processing, limiting their scalability and computational efficiency. They laid the foundation for more advanced architecture and developed modern NLP systems.

Figure 12: RNN, LSTM and GRU architecture (Idrees, 2024).

Figure 12: RNN, LSTM and GRU architecture (Idrees, 2024).

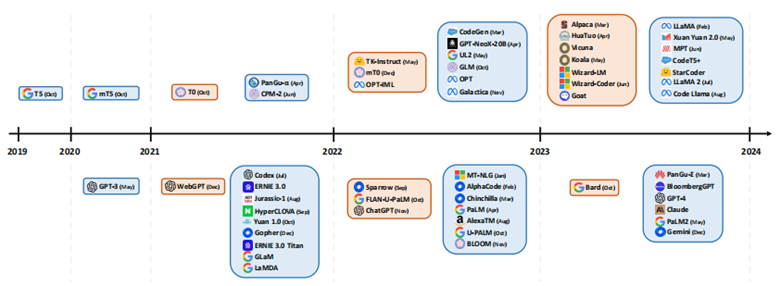

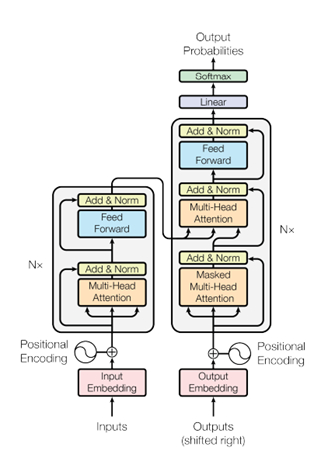

5.2.4.1.5. Modern Era: Transformers and Large Language Models

The introduction of the Transformer model marked a turning point for NLP. Transformers replaced the sequential nature of earlier models with a parallelized architecture, significantly improving scalability and performance (Vaswani et al., 2017). The core innovation of Transformers lies in their self-attention mechanism, which enables the model to focus on relevant parts of the input sequence while processing each token. This is achieved through the computation of attention scores, which determine the importance of words in relation to one another. Transformers also employ multi-head attention, allowing the model to capture multiple relationships within the data simultaneously. Another key feature is positional embeddings, which preserve the order of tokens in the sequence despite the parallelized processing.

Transformers became the foundation for Large Language Models (LLMs) such as BERT, GPT, and T5. These models scaled up the Transformer architecture, incorporating billions of parameters and training on massive datasets. Modern LLMs leverage contextual embeddings, where word representations vary depending on their context, enabling nuanced understanding and generation of text. For instance, GPT-3, with its 175 billion parameters, demonstrated unprecedented capabilities in generating coherent and contextually accurate text. The evolution of LLMs is illustrated in Figure 13, highlighting the rapid advancements in the field. Today, LLMs are the backbone of applications like chatbots, summarization tools, and automated translation systems, representing the cutting edge of NLP technology.

Figure 13: Evolution of Large Language Models.

Figure 13: Evolution of Large Language Models.

5.2.4.2. Architecture of Large Language Models

Large Language Models (LLMs) architecture is deeply rooted in the Transformer model introduced by (Vaswani et al, 2017). This revolutionary framework replaced sequential processing with parallel computation, enabling efficient handling of long text sequences. LLMs extend this foundational architecture to accommodate billions of parameters, allowing for complex understanding and generation of human language. Below is a detailed exploration of the key architectural components that make up LLMs.

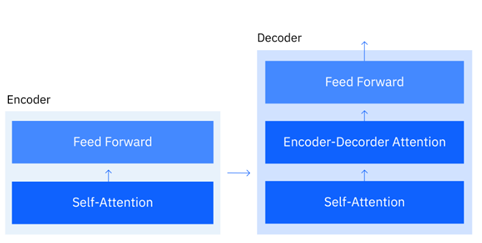

5.2.4.2.1. Encoders and Decoders

The Transformer model employs an encoder-decoder architecture to process and generate sequences. The encoder takes input text and converts it into a dense intermediate representation, while the decoder generates output text based on the encoder’s representation and its previous outputs (Figure 14). For tasks like machine translation, both encoders and decoders are critical. However, models like GPT use only the decoder stack for text generation tasks, which autoregressively predicts the next word given the previous context. Conversely, BERT relies exclusively on encoders to understand language, making it ideal for classification and sentence similarity tasks.

Figure 14: Encoder Decoder Architecture (Ph. D and Noble, 2024).

Figure 14: Encoder Decoder Architecture (Ph. D and Noble, 2024).

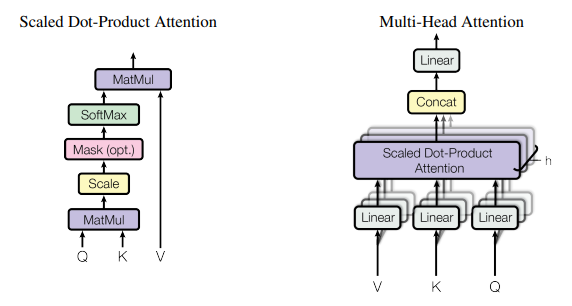

5.2.4.2.2. Attention Mechanism

At the heart of the Transformer is the attention mechanism, which allows the model to focus on the most relevant parts of the input sequence for each token being processed. Unlike traditional neural networks, where each input token is processed independently, attention mechanisms calculate relationships between all tokens in the sequence. The key operation in attention is

\[\mathrm{Attention}\left(Q,K,V\right)=\mathrm{softmax}\left(\frac{QK^T}{\sqrt{d_k}}\right)V\]Here:

Q(query),K(key), andV(value) are matrices derived from the input embeddings.d_kis the scaling factor (dimensionality of the keys).The output is a weighted combination of the values determined by the similarity between the query and the keys.

This mechanism enables the model to capture long-range dependencies in the text, such as relationships between words far apart in a sentence.

5.2.4.2.3. Contextual Embedding

Unlike earlier static embeddings such as Word2Vec, modern LLMs utilize contextual embeddings, where the meaning of a word is determined by its surrounding context. For instance, the word “bank” would have different embeddings in the phrases “river bank” and “money bank.” This dynamic understanding is achieved by stacking multiple attention layers and refining the token representations based on their context within the sequence. Contextual embeddings allow LLMs to understand nuanced language constructs, improving performance on summarization, sentiment analysis, and text generation tasks.

5.2.4.2.4. Multi-Head Attention

The Transformer incorporates multi-head attention to enhance the model’s capacity to learn diverse linguistic patterns (Figure 15). This involves projecting the query, key, and value matrices into multiple subspaces, performing attention operations independently for each subspace, and concatenating the results. Formally: \(\mathrm{MultiHead}\left(Q,K,V\right)=\mathrm{Concat}\left({\mathrm{head}}_1,\ldots,{\mathrm{head}}_h\right)W^O\)

Each head $ {\mathrm{head}}_i $ is computed as: ${\mathrm{head}}_i=\mathrm{Attention}\left(QW_i^Q,KW_i^K,VW_i^V\right)$

Here, $W_i^Q,W_i^K,W_i^V,W^O$ are learnable projection matrices. Multi-head attention allows the model to capture various types of relationships in the text simultaneously, such as syntactic dependencies and semantic similarities.

Figure 15: Attention Head architecture (Vaswani et al., 2017).

Figure 15: Attention Head architecture (Vaswani et al., 2017).

5.2.4.2.5. Transformer Architecture and LLMs

The Transformer (Figure 16) combines the above components into a unified framework by stacking multiple encoder and decoder layers. Each layer consists of two key sub-components:

Self-Attention Mechanism: Captures relationships within the input sequence.

Feed-forward Neural Networks: Applies non-linear transformations to refine token representations.

These layers are interleaved with residual connections and layer normalization, ensuring stable gradients during training. Modern LLMs build upon this architecture by scaling up the number of layers, embedding dimensions, and attention heads. For example:

GPT-3: Utilizes 96 decoder layers, 12 attention heads, and 175 billion parameters.

BERT: Features 12 encoder layers with 12 attention heads optimized for understanding tasks.

LLMs like GPT-3, BERT, and Llama are trained on diverse and massive datasets, leveraging techniques like masked language modelling and autoregressive text generation. These models have transformed NLP by enabling tasks such as conversational AI, text summarization, and language translation with unprecedented accuracy and fluency.

Figure 16: The Transformer - model architecture (Vaswani et al., 2017).

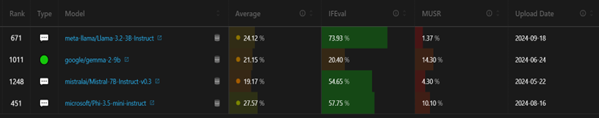

5.2.4.3. Model Selection for Text Generation

To fulfil the requirements of this project, Natural Language Processing (NLP) Large Language Models (LLMs) were utilized. In NLP, LLMs are designed for various tasks, such as text classification, question answering, translation, summarization, text generation, fill-mask, and sentence similarity. For this project, the primary focus was text generation, which aligns directly with developing a chatbot capable of generating accurate and contextually relevant responses to user queries. Text generation models are fine-tuned to predict the next word or token based on a given context, enabling them to produce coherent and meaningful responses. Several models were evaluated, and the following were chosen based on their compatibility, computational efficiency, and performance (Figure 17):

Phi-3.5-mini-instruct (Microsoft): A lightweight model optimized for instruction-based tasks, selected for its efficiency and ability to operate in resource-constrained environments.

Mistral-7B-v0.3 (MistralAI): Known for its balance between computational efficiency and performance, this model offers robust text generation capabilities.

Gemma-2-9B (Google): A benchmark model with 9 billion parameters, chosen for its high-quality text generation and contextual understanding.

-Llama-3.2-4B (Meta): A compact yet powerful open-source model with a strong performance in text generation tasks, selected for its computational feasibility and precision.

These models were carefully chosen to provide diverse capabilities, balancing computational efficiency and performance. Figure 16 presents a screenshot of the Open LLM Leaderboard from Hugging Face, showcasing the performance rankings of these models across various tasks.

Figure 17: The Open LLM Leaderboard from Hugging Face.

Figure 17: The Open LLM Leaderboard from Hugging Face.

5.2.4.3.1. Phi-3.5-mini-instruct

Developed by Microsoft, Phi-3.5-mini-instruct is a compact LLM with 3.5 billion parameters. This model is designed for instruction-based tasks and excels in environments with limited computational resources. It employs efficient attention mechanisms to process inputs, making it suitable for lightweight chatbot applications. Key Features:

Optimized for generating concise and contextually relevant responses.

Trained on diverse datasets to enhance generalizability.

High performance on instruction-following tasks with minimal computational overhead.

This model was selected for its ability to adapt to fine-tuning tasks with resource constraints

5.2.4.3.2. Mistral-7B-v0.3

Mistral-7B-v0.3, developed by MistralAI, is a mid-sized LLM with 7 billion parameters, balancing computational efficiency and task performance. The model leverages advanced optimizations like gradient checkpointing and low-rank adaptation, enabling fine-tuning on constrained hardware. Key Features:

Strong performance in text generation tasks, particularly for domain-specific fine-tuning.

Efficient memory utilization through mixed-precision training techniques.

Versatility across various NLP tasks, including chatbot development.

The inclusion of Mistral-7B ensures robust performance without excessive computational demands.

5.2.4.3.3. Gemma-2-9B

Gemma-2-9B, a benchmark model developed by Google, features 9 billion parameters, making it one of the most capable models for text generation tasks. This model is known for its ability to handle complex and context-sensitive queries, producing outputs with high fluency and coherence. Key Features:

Incorporates advanced attention mechanisms, enabling a nuanced understanding of context.

Designed for tasks requiring detailed and contextually rich outputs.

Offers state-of-the-art performance in text generation while maintaining scalability.

Despite its larger size, Gemma-2-9B was chosen for its superior quality in generating detailed responses, aligning with the chatbot’s requirements.

5.2.4.3.4. Llama-3.2-4B

Llama-3.2-4B, developed by Meta, is a lightweight yet high-performing LLM with 4 billion parameters. This model combines computational efficiency with robust text generation capabilities, making it ideal for real-world applications where resources may be limited. Key Features:

Compact architecture with high accuracy and contextual understanding.

Well-suited for generating concise and accurate chatbot responses.

Leverages efficient fine-tuning methodologies, reducing computational costs.

The Llama-3.2-4B model was selected for its compatibility with the project’s computational constraints and strong text generation task performance.

5.2.5. Dataset Formatting

Dataset formatting is crucial in preparing the training data for fine-tuning Large Language Models (LLMs). Different LLMs require specific input formats to identify the relationship between the user’s input and the model’s expected output. When a model is pre-trained, it is exposed to a defined structure that helps it interpret the input it receives and the response it generates. Adapting the dataset to the required format for fine-tuning is essential to ensure the model can effectively learn the relationships necessary for generating accurate outputs. This project utilised three distinct prompt formats, each tailored to the specific requirements of the models chosen for fine-tuning. These formats ensure compatibility with the pre-trained models and enhance their ability to generate contextually relevant and precise responses. The formats used are Alpaca Template, ChatML Format, and Jinja Template.

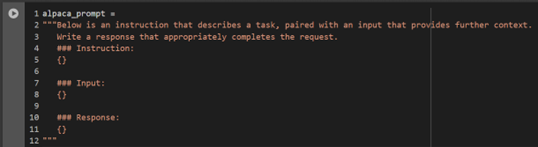

5.2.5.1. Alpaca Template

The Alpaca Template (Figure 18) is one of the most widely used prompt formats in the LLM fine-tuning community. It is designed to provide clear instructions to the model, helping it understand the task and context effectively. This format includes an instruction, an input, and a response. It is particularly suitable for models like Gemma-2-9B and Mistral-7B, trained to follow specific instructions in a structured format. The original dataset was converted into the Alpaca format, as shown in Figure 19, to align with the requirements of these models. The Alpaca prompt is structured as follows:

Figure 18: Alpaca prompt templates (Unsloth - Open source Fine-tuning for LLMs, 2024)

Figure 18: Alpaca prompt templates (Unsloth - Open source Fine-tuning for LLMs, 2024)

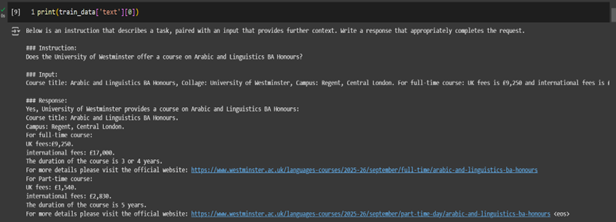

Figure 19: Formatted dataset for Gemma2 and Mistral model.

Figure 19: Formatted dataset for Gemma2 and Mistral model.

5.2.5.2. ChatML Format

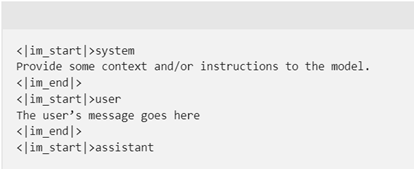

The ChatML Format (Figure 20) is an advanced and versatile structure that simulates natural conversations. Its key advantage is distinguishing between multiple roles in a dialogue, such as the system, user, and assistant. This format is particularly effective for building chatbots and conversational agents because it mimics real-world interactions, preserving the logical flow of a conversation. It was selected for fine-tuning Llama-3.2-3B and Phi-3.5-mini-instruct, optimized for chat-based applications requiring context-aware and coherent responses. The ChatML format provides a hierarchical structure to define different conversation roles. The system segment offers initial instructions or context to guide the model’s behaviour throughout the conversation. For example, the system could specify that the model should provide concise, formal, and accurate answers. The user segment contains the input query or prompt provided by the user. The assistant segment includes the model’s generated response to the user query. The structured format ensures that the model understands the flow and context of a multi-turn dialogue, which is critical for delivering meaningful and contextually relevant responses. An example of the ChatML format is shown in Figure 21

Figure 20: ChatML prompt template (mrbullwinkle, 2024).

Figure 20: ChatML prompt template (mrbullwinkle, 2024).

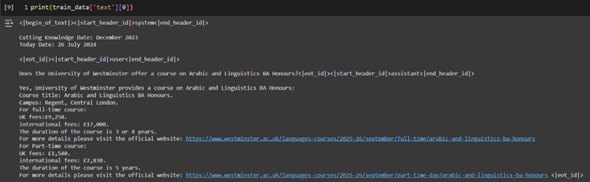

Figure 21: Formatted dataset for Llama-3.2 and Phi-3.5 model.

Figure 21: Formatted dataset for Llama-3.2 and Phi-3.5 model.

5.2.5.3. Jinja Format

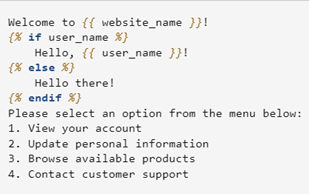

The Jinja Template (Figure 22 ) is a powerful and flexible format for generating dynamic text content. Originally designed as a templating language for web frameworks like Flask and Django, Jinja has proven an effective structure for creating structured prompts for LLMs, particularly when used on platforms like Ollama (Figure 23), which supports this format natively. The Jinja Template was selected for this project to fine-tune the model deployed on Ollama for local and cost-effective usage. Jinja templates are highly adaptable and well-suited for scenarios where dynamic content generation is required. For example, in this project, the chatbot must answer user queries about university programs by pulling specific fields like tuition fees, course duration, and campus location. Jinja templates enable this by embedding placeholders for these variables, making it possible to generate customized responses based on user input. The basic structure of a Jinja template includes Inheritance: Templates can inherit from base structures to maintain consistency across reactions. Blocks: Block directives can dynamically replace or extend Specific sections of content. Variables: Variables are enclosed in and can be dynamically replaced during runtime. Control Flow: Conditional logic and loops can be incorporated for more complex formatting.

Figure 22: An example of Jinja Prompt

Figure 22: An example of Jinja Prompt

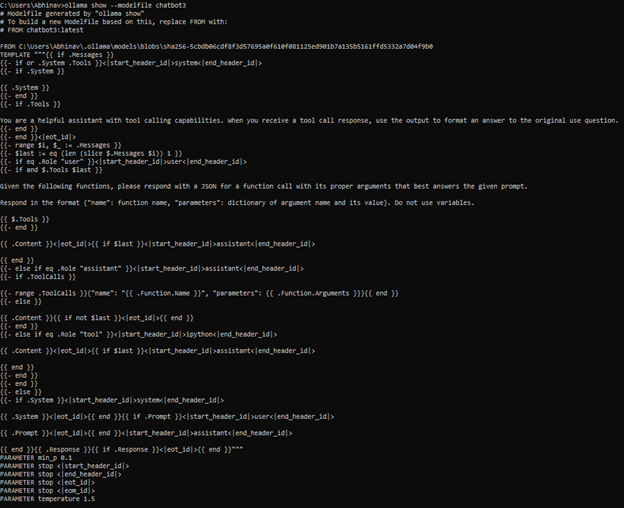

Figure 23: Actual Jinja Prompt used in Ollama.

Figure 23: Actual Jinja Prompt used in Ollama.

5.2.6. Model Training

Model training/fine-tuning is pivotal in customizing Large Language Models (LLMs) to generate accurate, domain-specific responses. This project involved fine-tuning four selected models Gemma-2-9B, Mistral-7B, Llama-3.2-3B, and Phi-3.5-mini-instruct using resource-efficient methodologies to align their capabilities with the requirements of the chatbot.

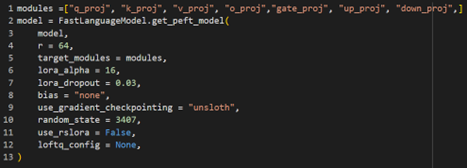

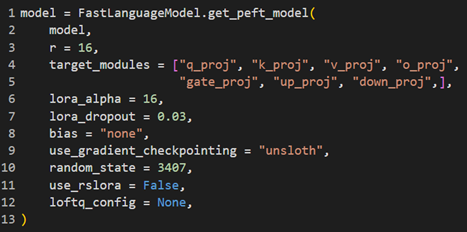

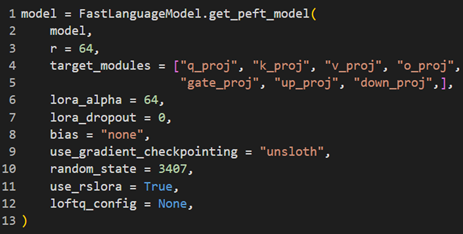

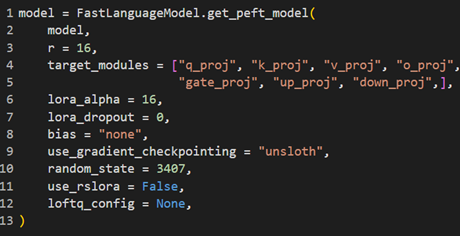

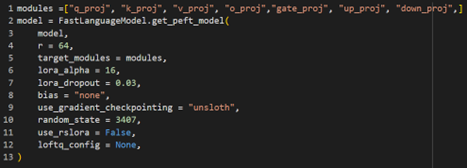

5.2.6.1. LoRA Adapters: Efficient Parameter Fine-Tuning

A key innovation in this project was using Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA) adapters, widely regarded as an efficient mechanism for fine-tuning large language models (Hu et al., 2021). LoRA bypasses the need to fine-tune all model parameters by introducing lightweight, task-specific layers. These layers are injected into specific parts of the model, drastically reducing the computational cost and memory requirements while maintaining high performance. LoRA Components:

Rank (

r): Determines the size of the low-rank matrices added to the model.Projection Modules: LoRA adapters are applied to specific projection layers of the Transformer, including:

q_proj,k_proj,v_proj: Represent the query, key, and value projections in the attention mechanism.o_proj: Handles the output projection of the attention layers.gate_proj: Controls gating mechanisms in specific model layers.up_projanddown_proj: Perform upscaling and downscaling of low-rank matrices.LoRA Alpha: A scaling factor used to adjust the impact of LoRA layers on the original model’s parameters.

LoRA adapters were particularly significant for this project, enabling models like Gemma-2-9B and Mistral-7B to be fine-tuned on limited hardware while achieving task-specific performance improvements. Table 1 provides a detailed configuration of LoRA parameters for each model, illustrating how these adapters optimized the training process for different architectures. The use of LoRA aligns with recent advancements in parameter-efficient fine-tuning, which have demonstrated substantial reductions in computational overhead while preserving the pre-trained knowledge of large models (He et al., 2022).

| LoRA Configuration of Models |

|---|

Model: gemma-2-9b Model: gemma-2-9b |

Model: mistral-7b Model: mistral-7b |

Model: Llama-3.2-3b Model: Llama-3.2-3b |

Model: Phi-3.5-mini-instruct Model: Phi-3.5-mini-instruct |

Table 1: Illustrating LoRA configuration used for all 4 selected models.

5.2.6.2. Downloading Pre-Trained Models to Local Runtime

The selected models, hosted on the Hugging Face Hub, were downloaded to the local runtime of Google Collab for fine-tuning. This approach minimized latency and ensured seamless model access during the training process. Each model’s size, download time, and hardware requirements are presented in Table 2, providing insights into the resource implications of fine-tuning different LLMs.

| Models download statistics |

|---|

Model: Gemma-2-9b Model: Gemma-2-9b |

Model: Mistral-7b Model: Mistral-7b |

Model: Llama-3.2-3b Model: Llama-3.2-3b |

Model: Phi-3.5-mini-instruct Model: Phi-3.5-mini-instruct |

Table 2: Represents the Downloading Statistics of Different models from the HuggingFace hub for finetuning.

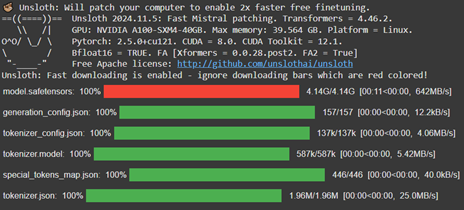

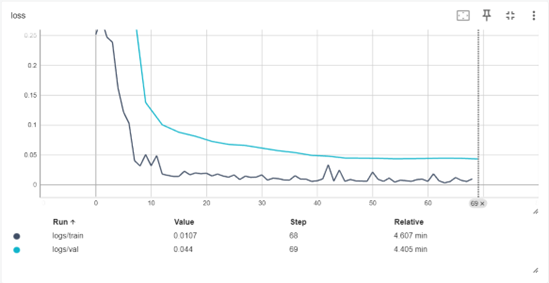

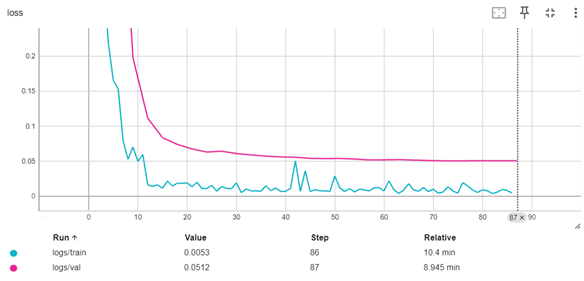

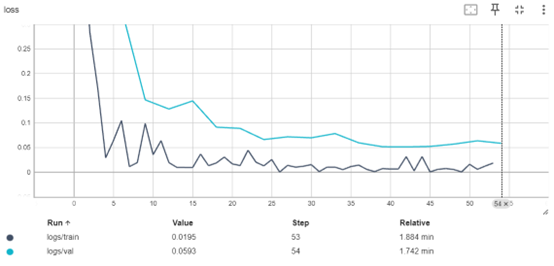

5.2.6.3. Implementation of Early Stopping

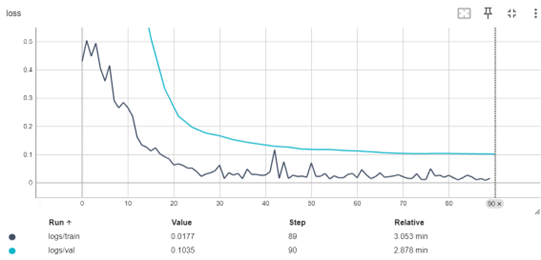

Early stopping was implemented during the training process to ensure robust model performance and prevent overfitting or underfitting. Early stopping monitors the validation loss at regular intervals and halts training when the loss no longer improves over a predefined number of steps (Goodfellow et al., 2016). This technique not only enhances model generalization but also minimizes unnecessary computational time. The implementation of early stopping for this project is depicted in Figure 24, which demonstrates the callback function integrated into the training pipeline. By dynamically adjusting the training duration, this approach ensured that the fine-tuning process yielded models optimized for accuracy and efficiency.

Figure 24: Implementation of early stopping callback

Figure 24: Implementation of early stopping callback

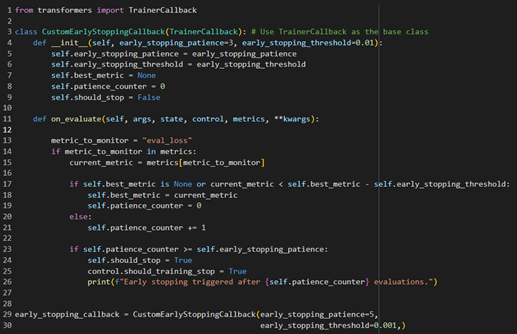

5.2.6.4. Training Parameters and Configuration

The fine-tuning process was managed using Hugging Face’s Trainer API with a custom configuration of training parameters. These parameters were carefully selected to balance computational efficiency with model performance:

Batch Size: A per_device_train_batch_size of

2was chosen to optimize memory usage during training.Gradient Accumulation: Steps set to

4allowed larger effective batch sizes without exceeding hardware memory limits.Warmup Steps: Gradual learning rate increases over 5 steps ensured model stability during the initial phase of training.

Learning Rate: A learning rate of

2e-4was used to facilitate stable convergence, aligning with recommended practices for large-scale models (Brown et al., 2020).Mixed Precision Training:

FP16andBF16precision modes were toggled based on GPU support to reduce memory usage and accelerate computation.Evaluation Strategy: Validation was performed every 3 steps (

eval_steps=3), with the best-performing model checkpoint loaded at the end of training.Optimization Algorithm: The AdamW optimizer with 8-bit precision (

adamw_8bit) was employed for efficient weight updates and memory savings.

The training script, as shown in Figure 25, demonstrates the integration of these parameters within a customized pipeline.

Figure 25: Implementation of Training parameters

Figure 25: Implementation of Training parameters

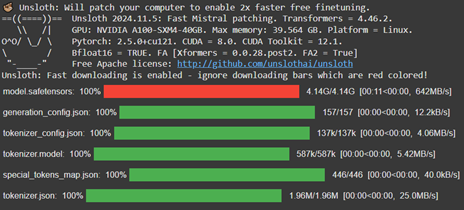

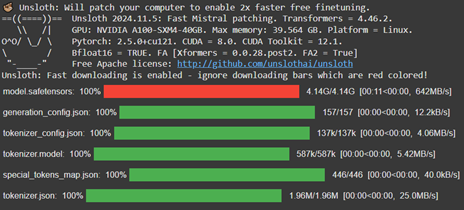

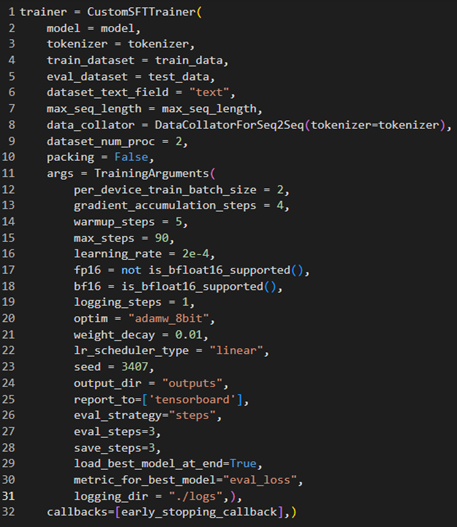

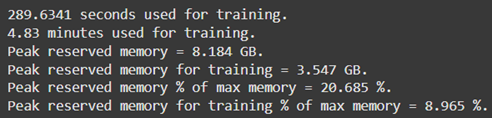

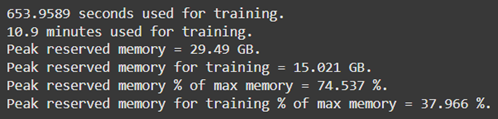

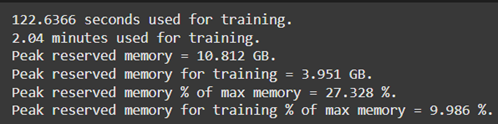

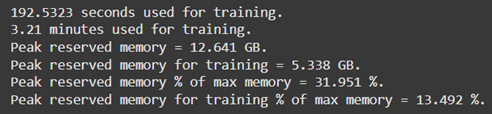

5.2.6.5. Resource Optimization Using Unsloth and Google Collab

The Unsloth library addressed the computational challenges of fine-tuning large-scale models. Unsloth optimizes GPU utilization by reducing memory overhead through parameter-efficient techniques, making it a suitable choice for fine-tuning in constrained hardware environments (Hu et al., 2021). The training was conducted on Google Collab, leveraging its provision of high-performance GPUs, such as the NVIDIA A100, which supports mixed-precision training for faster and more efficient computation. The efficiency of GPU memory usage during the training of all four models is summarized in Table 3, demonstrating significant reductions in resource consumption through Unsloth. This optimization was critical for fine-tuning models with billions of parameters while operating within the constraints of cloud-based hardware.

| GPU Memory usages |

|---|

Model: Gemma-2-9B Model: Gemma-2-9B |

Model: Mistral-7B Model: Mistral-7B |

Model: Llama-3.2-3B Model: Llama-3.2-3B |

Model: Phi-3.5-Mini-Instruct Model: Phi-3.5-Mini-Instruct |

Table 3: Memory optimization using Unsloth, Google Collab and Nvidia A100 GPU.

5.2.6.6. Saving and Deployment of Fine-Tuned Models

After completing the training process, the fine-tuned models were saved with 16-bit precision to reduce storage requirements without compromising inference performance. These models were uploaded to the Hugging Face Hub, making them accessible for further evaluation and deployment (Figure 26). Reduced precision aligns with best practices for deploying LLMs in resource-constrained environments (Rajbhandari et al., 2020).

Figure 26: All the finetuned Models uploaded to HuggingFace Hub.

Figure 26: All the finetuned Models uploaded to HuggingFace Hub.

5.2.7. Model Evaluation

Evaluating the performance of Large Language Models (LLMs) poses unique challenges, as traditional evaluation metrics often fail to capture the nuanced capabilities of these models. Unlike standard machine learning models, which can be assessed using metrics such as accuracy or precision, LLMs require evaluation methods tailored to their specific type and task. This project chose several task-appropriate metrics to evaluate comprehensively the fine-tuned models’ effectiveness in generating accurate, contextually relevant, and coherent responses.

5.2.7.1. Limitations of Traditional Metrics

Traditional evaluation metrics, such as accuracy or F1-score, are insufficient for LLM evaluation due to the generative nature of these models. Generative models, particularly those tasked with natural language responses, do not produce binary outcomes or fixed labels. Instead, they generate open-ended outputs that require evaluation based on multiple dimensions, including fluency, relevance, coherence, and factual accuracy (Celikyilmaz et al., 2020). Therefore, specialized metrics are required to capture the complexity of LLM-generated text.

5.2.7.2. Selected Metrics for Model Evaluation

Based on the type and task of the LLMs in this project, the following evaluation metrics were employed:

5.2.7.2.1. BLEU (Bilingual Evaluation Understudy)

The BLEU metric evaluates the similarity between the model’s generated response and a set of reference responses. BLEU scores are calculated based on the overlap of n-grams (sequences of words) between the generated and reference texts, with higher scores indicating closer alignment. Formula: \(\mathrm{BLEU}=BP\cdot\exp{\left(\sum_{n=1}^{N}w_n\log{p_n}\right)}\)